Innovations for decarbonising heavy-goods vehicle mobility

A key sector for the economy and a real source of jobs, transport of goods by road is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. In France and elsewhere, decarbonisation of this sector will be a significant challenge for the coming years in order to limit climate change. To achieve this, stakeholders in the sector are innovating.

Transport: top contributor to greenhouse gas emissions

Unlike other economic sectors, road transport is the only one whose greenhouse gas emissions have continued to increase in France since 1990. In France it is responsible for 30% of total national greenhouse gas emissions, ahead of farming and silviculture and the manufacturing and construction industry. At the European level, it is estimated that heavy-goods vehicle mobility accounts for almost one third of transport-related CO2 emissions.

Tightening of legislation

On 21 November, 2023, the European Parliament ruled that from 2030, new heavy-goods vehicles sold must emit 45% fewer CO2 emissions than those sold in 2019. This threshold increases to 65% for 2035 and 90% for 2040.

These measures are part of a goal to decarbonise the economy overall: the European Green Deal, which aims for a 55% net reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared with 1990.

In addition to the improved aerodynamics of vehicles and the optimisation of journeys, to avoid empty or “road waste” journeys (only half of all lorries in France travel with a full load), vehicle makers and road infrastructure managers are innovating to decarbonise heavy-goods mobility.

Alternatives to the thermal combustion engine

Given the imminent deadline, experiments and innovations to replace the thermal combustion engine (running on diesel) are accelerating. Alternative fuels and electric engines, how will the heavy-goods vehicles of the future operate: hydrogen, biogas or electric battery?

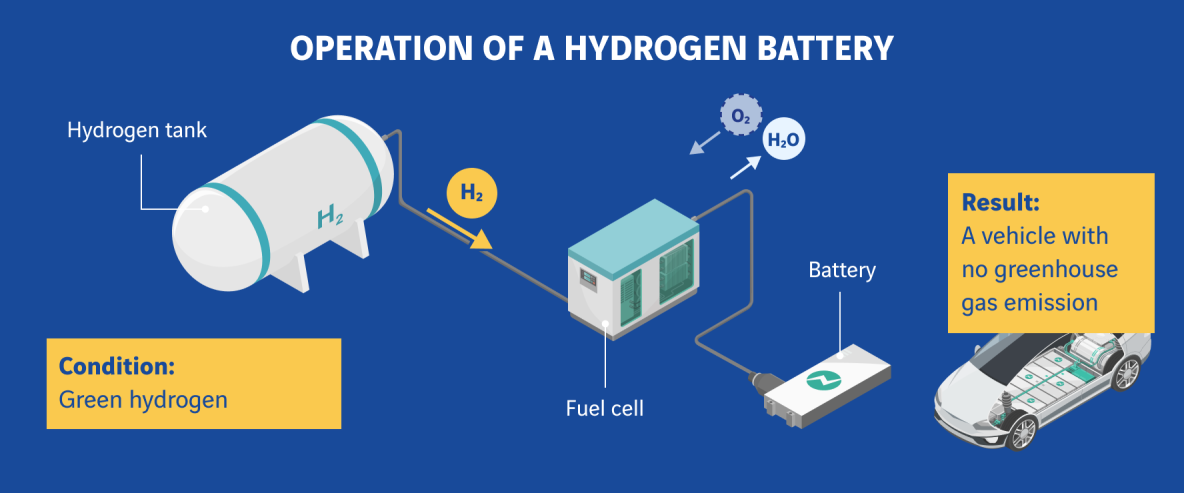

Hydrogen vehicles

Hydrogen vehicles operate with a fuel cell supplied by hydrogen and molecular oxygen. The electromagnetic reaction between these two gases in the fuel cell produces energy that supplies the battery and the vehicle’s engine. The benefit is that the vehicle emits no greenhouse gas. The drawback is that for this use of hydrogen to be green, it must be produced from renewable energy sources and requires massive roll-out of charging terminals throughout the country. Today a hydrogen-powered lorry would cost over four times the price of equivalent combustion engine vehicles.

The emergence of bio-fuels

Operating heavy-goods vehicle on biogas is also a more ecological option than diesel, and is also renewable. Biogas is produced from methanisation of organic waste.

The arrival of electric heavy-goods vehicles

Electric engines are developing fast and are very promising.

But the development of this process for heavy-goods vehicles comes with major limitations, tied to the weight and size of batteries and their range. The batteries weight several tonnes and affect the vehicle’s performance and its payload. Furthermore, their range - for vehicles that travel long distances daily - is also a factor to consider, and which requires massive roll-out of charging terminals throughout the country, in carrier depots, on the outskirts of logistics areas and along main road systems, as well as good stability of the electrical grid.

Dynamic charging systems, the future of road freight?

The limits of electric engines could be overcome by ingenious “dynamic charging” technologies, known as Electric Road Systems (ERS). The principle is simple and enables an electric lorry to charge its battery while driving. The batteries take over for the rest of the journey, when there is no ERS system.

There are three technologies...

- Inspired by rail travel, overhead catenary charging – via electric supply cables - can be adapted to the road. Lorries fitted with pantographs can be charged as they pass, and then continue to their destination, via a combustion or electric engine relay.

- A less restrictive option - since there are no live overhead cables, induction charging, is also gaining ground. Induction plates built below the road surface and in vehicles enables the lorry batteries to be supplied and charged when moving via the electromagnetic fields of the induction coils

- Option three: conductor rail power supply, developed originally for tramways, and which can be adapted to road transport, where journeys are in less of a straight line.

ERS, full-scale testing

Selected by BPI France from a call for projects, an experiment launched by a consortium of companies led by VINCI Autoroutes will test two of these dynamic charging technologies.

For a period of three years, the Charge As You Drive project will test induction and rail charging on the A10 motorway in France, once certain hypotheses have been tested in closed-circuit tests.

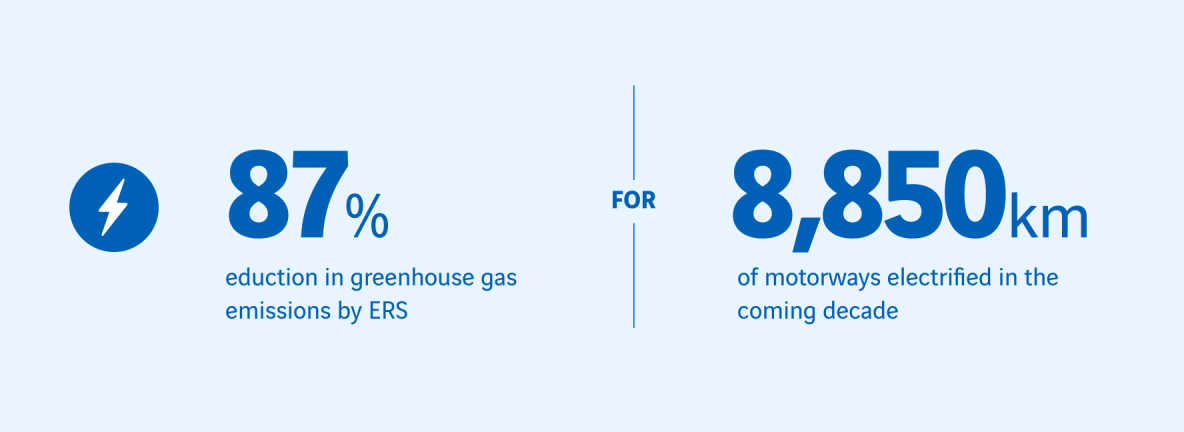

In France, ERS could enable a drastic reduction in CO2 emissions. In a report published in 2021, the Ministry for Transport estimated this reduction to be 87% in comparison with the current model, operating mainly on diesel, and provided that 8,850 km of motorways and national roads are electrified in the coming decade.

Limitations and synergies of decarbonising solutions

Dynamic charging solutions also present limitations. Besides the need for the afore-mentioned overhead cables, the construction of these infrastructures requires large-scale investment, estimated in France at between 30 and 35 billion euros. In comparison, government allocations to assist the sector seem for the moment to be modest. Climate conditions, high rainfall or low temperatures, also impact their performance.

It is likely that a combination of solutions will be the key to achieving the decarbonisation goals set.

Most viewed

Explore more

Words from researchers: let's fight stereotypes!

Charlotte, a research fellow at École des Mines, and Erwan, a university professor and researcher at AgroParisTech, talk…

Fondation VINCI pour la Cité: opening the door to others is another way of reaching out!

With some 1.3 million organisations and 2 million employees, France can lay claim to a dynamic network of associations…

Sea water desalination: a solution for turning the tide on the water scarcity crisis?

As water shortages continue causing havoc in a growing number of regions around the world, an age-old idea is experiencing a…