New Zealand: a metro on the road to social reconciliation

City Rail Link is New Zealand's biggest urban infrastructure project. Auckland's first underground metro will promote the development of the city and low-carbon mobility in this metropolis of one and a half million inhabitants. In addition to the expected benefits of the infrastructure, the project is a real social success story, involving the Māori population right from the design stage.

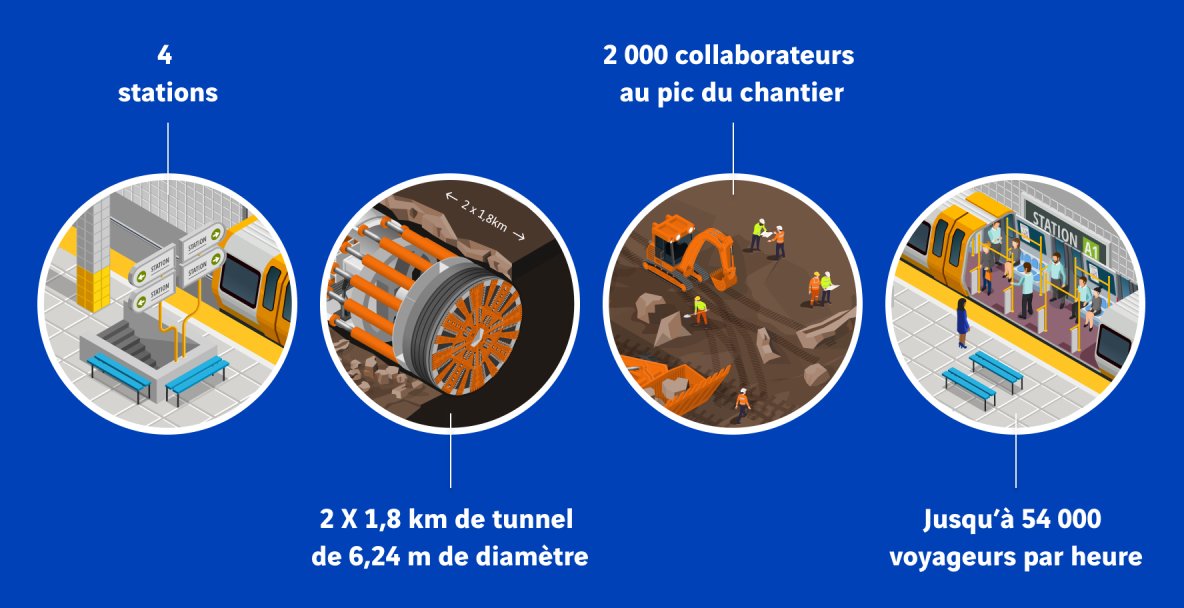

Carried out by VINCI Construction under an original contractual framework known as an alliance with the public project owner and partners (Link Alliance), the project aims to make up for the lack of public transport in Auckland, the country's economic capital. The infrastructure is needed to facilitate the sustainable growth of the city. Once completed, the City Rail Link will connect two pre-existing stations in the north and south of the city, doubling the number of people living within half an hour's travel of the city centre.

Beyond the technical challenges, the project has proved to be a success story of social integration and cooperation with the Māori community in a country whose colonial history has long ostracised indigenous populations.

Berenize Peita, Legacy and Social Impact Manager for Link Alliance explains.

How is City Rail Link a project that serves New Zealand's social pact?

Our country has a turbulent colonial past, and its first inhabitants have long been denied the recognition they rightfully deserve. Things have started to change, but there is still a long way to go to redress the balance in favour of the Māori, who are over-represented among groups experiencing social, economic, educational and other difficulties. In the early 2010s, a project on the scale of City Rail Link was a step towards a turning point. In a rare occurence at the time, the Māori community was consulted from the outset of the project. Eight iwis (Iwi is the main social unit in Māori society and approximately translates as clan’ or ‘tribe’. New Zealand has 35 iwis, recognised by the government and exercising certain political responsibilities) decided to become involved: they now take part in regular monitoring meetings and have greatly influenced the vision, values and even the aesthetics of the project, whose architecture and names of structures are inspired by Māori culture.

What practical steps have been taken to turn this project into a lever for the social and economic integration of the Māori people?

We're working on three main levels. Firstly, employment, with a tailored recruitment programme aimed at Māori and Polynesian people, particularly young people who left school early. Secondly: training. The aim is not only to offer jobs at all skill levels, but also to ensure that these employees develop their careers and acquire new skills through a progressive employment plan. Finally, there are economic benefits of the project itself. We have set up a programme that directs 10% of purchases to Maori and Pasifika owned businesses. This applies to all areas, including site subcontracting.

Atarangi, who began her career on City Rail Link as a trainee under the project's rolling employment scheme, is now an environmental officer and is completing a degree in science.

What do you see as the legacy of this project?

Our pioneering approach now serves as a benchmark for other projects. Contrary to what often happens in this type of programme, where some companies only leave the built environment, VINCI Construction played the game and shared its knowledge and skills widely. In particular, I'm convinced that the young people we support will see more opportunities open up for them: we've been able to broaden their horizons and show them that public works is a beautiful profession.

Most viewed

Explore more

Words from researchers: let's fight stereotypes!

Charlotte, a research fellow at École des Mines, and Erwan, a university professor and researcher at AgroParisTech, talk…

Fondation VINCI pour la Cité: opening the door to others is another way of reaching out!

With some 1.3 million organisations and 2 million employees, France can lay claim to a dynamic network of associations…

Sea water desalination: a solution for turning the tide on the water scarcity crisis?

As water shortages continue causing havoc in a growing number of regions around the world, an age-old idea is experiencing a…